In 2012, as I waited for Taj Mahal Foxtrot to roll off the presses, I burnt some nervous energy by trying to tame the mountain of research material that had grown steadily by the side of my computer over the previous years.

I had amassed all sorts of ephemera. I had music in seven formats (78s, 45s, LPs, spool tape, cassettes, CDs and digital files). I had newsletters issued by a short-lived association of Indians performing western music in the 1940s, the menu of the offerings at the Taj on Independence Day, 1947, and dozens of clips from The Chicago Defender.

I had a guidebook to Shanghai from 1935, a monograph on Gandhi’s influence on the US Civil Rights Movement and almost everything written by that feisty commentator DF Karaka.

As I got to the bottom of the pile, I found two treasures I’d forgotten about: Jazz Album Covers: The Rare and the Beautiful and David Stone Martin: Jazz Graphics. Both of them were written by Manek Daver, a businessman who spent much of his life in Japan.

Though Taj Mahal Foxtrot is the first book about Indian jazz, Daver is the first Indian to have written books related to jazz.

Daver grew up in Bombay and started collecting records shortly after the end of World War II (as he wrote, “You buy your first record, you are a collector” ). His first records were 78s and, as was the convention in India in those days, they came in brown-paper sleeves. “An individual 78rpm sold for the Indian equivalent of 50 American cents, which certainly did not justify the record company designing a sleeve for a particular record,” he wrote.

When LPs became the norm in the 1950s, designing the covers of jazz records posed several particular challenges for graphic designers, Daver noted in Jazz Album Covers. For one, “many of the jazz musicians recording were new faces who were not immediately recognisable and often lacked a photogenic personality”.

On 78rpm records, listeners had grown accustomed to three-minute versions of songs. With LPs, each track was longer, with improvisations and solos. LP covers needed to explain the recording and convey the special ambiance of the album. “How would the designer transport the music into his medium, possess it, clothe it and then send it back to the real world?” Daver asked.

In his book about David Stone Martin, Daver records that the illustrator was actually baptised David Livingstone Martin but changed his name because he got tired of his schoolmates repeating the crack, “Dr Livingstone, I presume?” Martin’s designs for jazz labels were so cherished, they were exhibited at several institutions, including at the Metropolitan Museum and MoMA in New York and the Art Institute of Chicago.

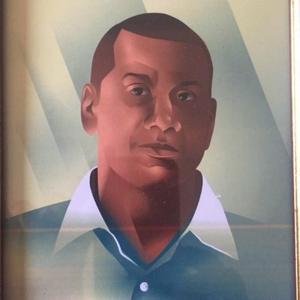

India doesn’t really have a tradition of jazz album art, but in the early 1950s, a young artist named Mehlli Gobhai began to do illustrations for the covers of the short-lived jazz magazine Blue Rhythm. He was inspired by record covers by such artists as DSM, whose work he saw in magazines at the USIS.

He also drew situations he saw around him. The girl listening to that portable gramophone player, for instance, is Usha Amin, who would go on to become the wife of adman Kersy Katrak. When Gobhai drew her, she was a member of Theatre Group, and was in the chorus of Murder in the Cathedral. (Gobhai was a knight.)

Gobhai was an invaluable source for stories about the Blue Rhythm gang: editor Niranjan Jhaveri and also about his two assistant editors, Jehangir Dalal and Coover Gazder. He also had hilarious tales to recount about taking tango lessons at McDonald’s school of dance, above Regal cinema, recalling with horror the instructor with sweaty armpits who held him tight as she demonstrated the steps.

Gobhai was kind enough to allow me to reproduce the Blue Rhythm covers in my book. (His paintings now sell for lakhs of rupees.)

Write a comment ...