In April, after lying in the vaults for nearly four decades, Amancio D'Silva's album Sapna finally made its way into the world. Accompanied by sitarist Clem Alford, tabla player Jahlib Millar and saxophonist/flautist Lyn Dobson, D'Silva "construct[s] a deeply evocative set transcending the realm of both jazz and Indian music", says the label behind the release.

You can listen to the tracks and buy them on Bandcamp.

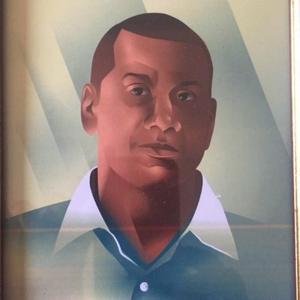

Here's a piece I wrote about D'Silva in 2005.

In 2004, in a review of an album called Integration, the Guardian declared, “Of all the attempts to bring together jazz and Indian music, this must be one of the most successful…[The tunes] strike a perfect balance between the two idioms, and there is none of that phoney ‘Eastern’ flavouring, featuring sitars and such like…the music swings in a completely natural way.”

The album under consideration had actually been released 35 years earlier, but had been reissued after a fortunate series of events – bringing Bombay-born guitar player Amancio D’Silva back into the spotlight eight years after he’d passed away.

The Amancio revival gathered pace a few months later with the issue in the UK of Konkan Dance, an album recorded in 1974 that inexplicably had never been published before. Predating by several years the now-celebrated fusion sounds of Shakti and running almost parallel to the efforts of American saxman John Coltrane’s far-better-known efforts to use an Indian approach to jazz improvisation, the five albums D’Silva recorded between 1969 and 1972 were finally being accorded their rightful place in jazz history.

The titles of D’Silva’s compositions give a clue to the things that are important to him: “Jaipur” and “Maharani” pay homage to his mentor Gayatri Devi, “Joyce Country” is named for this wife, “What Maria Sees”, “Song for Francesca” and “Stephano’s Dance” are named for his children, while the Konkan Dance album opens with a tune about the city of his birth, “A Street in Bombay”.

The rediscovery of D’Silva’s work started in 2003, when BBC Radio 1 DJ Giles Petersen included his track “Jaipur” on a collection of underground and progressive British jazz from the ’60s, and the momentum increased when Impressed with Gilles Petersen Vol 2 the next year featured “A Street in Bombay”. Months later, Universal decided to re-release Integration, an album that featured Hindustani-tinged tunes composed by D’Silva and performed along with some of the most cutting-edge British jazzmen of the time.

The enthusiasm of the Guardian’s reviewer only echoed the opinion that critics had expressed when the record was first released. “The compositions…reflect his preoccupation with effecting an Indian music-jazz blend,” the influential Melody Maker magazine said of D’Silva in 1970. “Since Coltrane, this has been a vogue… D’Silva’s grasp of both styles ensures that his blend is far more authentic than a lot of the jazz-raga which is hawked about. His playing too has an individual stamp.”

The renewed interest in Amancio D’Silva’s music thrilled his family. “I just dig that the music can get to the people who might dig it,” D’Silva’s son, Stephano, told me in an email interview from London. “The rest is just a by product of the real thing.”

The Amancio revival was also being being keenly followed in Bombay, where D’Silva grew up. “I’m very proud of my brother,” his sister Antoinette Fernandes, who lives in Bandra, told me. Added Raymond Albuquerque, who got his first job playing drums in a quartet led by Amancio D’Silva at Juhu’s Sun and Sand hotel in 1965, “He was in a league of his own. I heard [British guitar great] John McLaughlin when he played in Bombay with [pioneering mid-1970s world music group] Shakti, but I didn’t find it outstanding because I’d already hear Amancio. He was really ahead of his time.”

Amancio D’Silva’s journey started in Parel. The son of an employee of Kohinoor Mills, he was the only brother in a family with five daughters, all of whom had names beginning with the letter A. His sister Antoinette recalls that he displayed an early talent for music, and that his interest was nurtured by an uncle named John Carvalho, who played in a band called the Highhatters. Carvalho helped D’Silva to learn how to play the banjo, though the boy later moved on to the guitar. His skills were sharpened when he joined the band at his school, Don Bosco’s in Matunga. Soon after, he was playing at Parsi weddings and at gymkhanas with the much-loved Nellie and her Swing Band.

By his early twenties, Antoinette Fernandes said, her brother was touring with his own group, playing in Delhi, Nanital and Missourie. D’Silva probably sharpened his ear for Hindustani sounds when he, like many Goan jazz musicians of his age, worked in Hindi films studios by day, to supplement his income from jazz clubs. Among others, D’Silva worked with Laxmikant and Pyrelal. At any rate, he was already playing Indian-influenced jazz by 1965, when he led a group called the Sundowners at the Sun and Sand. “He had his own style of playing the guitar,” said drummer Raymond Alburque. “His technique was superb. He’d composed numbers in raga forms. He was that obsessed with music. Sometimes, he’d get up in the middle of the night to play new ideas.”

On one of his gigs up north, playing at a restaurant named Davico’s in Simla, D’Silva met his future wife, an Irish woman named Joyce who was teaching at a Catholic convent school in the hill station. After they got married, D’Silva and his family (which now included his baby daughter Maria) moved to Jaipur, where he played at the Rambagh Palace Hotel. “Amancio became an unusual choice of court musician for the Maharani, Gayatri Devi, leading a jazz/dance band at the palace,” Stephano D’silva says on a website he’s compiled about his father. “It was the Maharani who bought Amancio his first quality western-built instrument, a Gibson (apparently a semi-acoustic), which she picked up for him while on a trip to the US.”

By 1966, D’Silva was in Delhi, playing under the legendary saxophonist Braz Gonsalves at a venue called Laguna. It’s likely that this stint had a deep influence on the sounds he made later, because Gonsalves was intensely exploring raga-based jazz. “This thing had just started, trying to improvise on ragas,” Gonsalves recalled. “Our music was actually for the future – when I see what’s happening now, we’d already done it at that time. It was really creative music.”

But shortly after, D’Silva’s newly born son, Stephano, was discovered to have an acute blood condition. Antoinette Fernandes says that it was Gayatri Devi who suggested that D’Silva seek treatment in England, and who paid for his son’s treatment, as well as the move. The D’Silvas arrived in London in the spring of 1967.

It wasn’t easy at first. Amancio D’Silva worked as cleaner and as a musician at a pub in east London called the Prospect of Whitby, before he found gigs in other clubs. His break came when he attracted the attention of a record producer named Denis Preston, the man the Grove Encyclopaedia of Music credits with coining the term “fusion”. “Denis was teaming unique musicians from the folk and jazz idioms and, with a rare emphasis on artistic freedom, recording these collaborations for his company, Record Supervision,” Stephano D’Silva says in his liner notes for Konkan Dance.

The first of those efforts, Integration, lined up D’Silva alongside trumpet player Iain Carr and saxophone player Don Rendell, among others. “This one of the most effortless and natural albums that I’ve ever helped to make,” Carr wrote on the sleevenotes to Integration. “From the moment Denis Preston introduced me to Amancio D’Silva, a kind of dreamlike inspiration seemed to pervade our whole relationship and ideas for our project arrived out of nowhere…It is his feelings for both musical traditions – Indian and jazz – that makes a logical integration possible in this album. His melodic flair is Indian, but…he swings like a jazzman.”

The period also saw D’Silva trading ideas on an album called Hum Dono with Jamaican-born saxophonist Joe Harriott, who only a few years earlier had recorded two albums with Calcutta-born violin player John Mayer titled the Indo-Jazz Suites. “I think my father had a great deal of respect for [Joe Harriott] as a musician, and felt quite deeply for him as a person,” Stephano D’Silva said. “His passing upset my father very much.”

Stephano D’Silva emphasised that his father’s burst of recording activity “was also a period necessitating financial creativity, driven by the need to feed and clothe his family”. He explained, “He was not living in any bourgeois artistic idyll that some may assume musicians of that time were.”

Konkan Dance in 1974 was D’Silva’s last recording for Preston. “For reasons unknown, it never saw a release in spite of the fact that artwork was prepared for it,” Stephano D’Silva writes in his liner notes. “What remains is a ¼ inch studio tape copy, thankfully in perfect condition, given to Amancio in the mid-1970s by Denis, whose enterprise at [the Lansdowne recording studios in London’s Holland Park] also ended around the same time.” Stephano D’Silva says his father stopped recording because he “was a bit fed up” that his company was not “forthcoming on royalty issues”.

Still, he continued to perform, stopping only when forced to by a series of severe strokes. But even that didn’t stop him teaching, said Stephano D’Silva. Amancio D’Silva initially taught at Jenako Arts, in London’s East End and later at the Krishnamurti International School in Hampshire. In an interview to Jazz Journal shortly before has passed away in 1996, D’Silva made it clear that he believed emotion was far more important than technique. “Technically, today we are miles ahead, but…no feeling,” he said. “Why do they have to go play jazz? Jazz is something from the heart.”

Stephano D’Silva suggests that his father would perhaps be surprised at the posthumous praise being heaped upon him. “I hardly heard my father use terms such as fusion, jazz, crossover, and so on,” he said. “He had little to say. He just played.”

There's much more on the official Amacio D'Silva site.

Write a comment ...